Sectional curvature

In Riemannian geometry, the sectional curvature is one of the ways to describe the curvature of Riemannian manifolds. The sectional curvature K(σp) depends on a two-dimensional plane σp in the tangent space at p. It is the Gaussian curvature of that section — the surface which has the plane σp as a tangent plane at p, obtained from geodesics which start at p in the directions of σp (in other words, the image of σp under the exponential map at p). The sectional curvature is a smooth real-valued function on the 2-Grassmannian bundle over the manifold.

The sectional curvature determines the curvature tensor completely.

Contents |

Definition

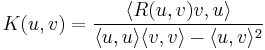

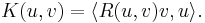

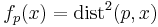

Given a Riemannian manifold and two linearly independent tangent vectors at the same point, u and v, we can define

Here R is the Riemann curvature tensor.

In particular, if u and v are orthonormal, then

The sectional curvature in fact depends only on the 2-plane σp in the tangent space at p spanned by u and v. It is called the sectional curvature of the 2-plane σp, and is denoted K(σp).

Manifolds with constant sectional curvature

Riemannian manifolds with constant sectional curvature are the most simple. These are called space forms. By rescaling the metric there are three possible cases

- negative curvature −1, hyperbolic geometry

- zero curvature, Euclidean geometry

- positive curvature +1, elliptic geometry

The model manifolds for the three geometries are hyperbolic space, Euclidean space and a unit sphere. They are the only complete, simply connected Riemannian manifolds of given sectional curvature. All other complete constant curvature manifolds are quotients of those by some group of isometries.

If for each point in a connected Riemannian manifold (of dimension three or greater) the sectional curvature is independent of the tangent 2-plane, then the sectional curvature is in fact constant on the whole manifold.

Toponogov's theorem

Toponogov's theorem affords a characterization of sectional curvature in terms of how "fat" geodesic triangles appear when compared to their Euclidean counterparts. The basic intuition is that, if a space is positively curved, then the edge of a triangle opposite some given vertex will tend to bend away from that vertex, whereas if a space is negatively curved, then the opposite edge of the triangle will tend to bend towards the vertex.

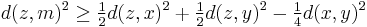

More precisely, let M be a complete Riemannian manifold, and let xyz be a geodesic triangle in M (a triangle each of whose sides is a length-minimizing geodesic). Finally, let m be the midpoint of the geodesic xy. If M has non-negative curvature, then for all sufficiently small triangles

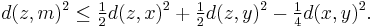

where d is the distance function on M. The case of equality holds precisely when the curvature of M vanishes, and the right-hand side represents the distance from a vertex to the opposite side of a geodesic triangle in Euclidean space having the same side-lengths as the triangle xyz. This makes precise the sense in which triangles are "fatter" in positively curved spaces. In non-positively curved spaces, the inequality goes the other way:

If tighter bounds on the sectional curvature are known, then this property generalizes to give a comparison theorem between geodesic triangles in M and those in a suitable simply connected space form; see Toponogov's theorem. Simple consequences of the version stated here are:

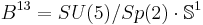

- A complete Riemannian manifold has non-negative sectional curvature if and only if the function

is 1-concave for all points p.

is 1-concave for all points p. - A complete simply connected Riemannian manifold has non-positive sectional curvature if and only if the function

is 1-convex.

is 1-convex.

Manifolds with non-positive sectional curvature

In 1928, Élie Cartan proved the Cartan–Hadamard theorem: if M is a complete manifold with non-positive sectional curvature, then its universal cover is diffeomorphic to a Euclidean space. In particular, it is aspherical: the homotopy groups  for i ≥ 2 are trivial. Therefore, the topological structure of a complete non-positively curved manifold is determined by its fundamental group. Preissman's theorem restricts the fundamental group of negatively curved compact manifolds.

for i ≥ 2 are trivial. Therefore, the topological structure of a complete non-positively curved manifold is determined by its fundamental group. Preissman's theorem restricts the fundamental group of negatively curved compact manifolds.

Manifolds with positive sectional curvature

Little is known about the structure of positively curved manifolds. The soul theorem (Cheeger & Gromoll 1972; Gromoll & Meyer 1969) implies that a complete non-compact non-negatively curved manifold is diffeomorphic to a normal bundle over a compact non-negatively curved manifold. As for compact positively curved manifolds, there are two classical results:

- It follows from the Myers theorem that the fundamental group of such manifold is finite.

- It follows from the Synge theorem that the fundamental group of such manifold in even dimensions is 0, if orientable and

otherwise. In odd dimensions a positively curved manifold is always orientable.

otherwise. In odd dimensions a positively curved manifold is always orientable.

Moreover, there are relatively few examples of compact positively curved manifolds, leaving a lot of conjectures (e.g., the Hopf conjecture on whether there is a metric of positive sectional curvature on  ). The most typical way of constructing new examples is the following corollary from the O'Neill curvature formulas: if

). The most typical way of constructing new examples is the following corollary from the O'Neill curvature formulas: if  is a Riemannian manifold admitting a free isometric action of a Lie group G, and M has positive sectional curvature on all 2-planes orthogonal to the orbits of G, then the manifold

is a Riemannian manifold admitting a free isometric action of a Lie group G, and M has positive sectional curvature on all 2-planes orthogonal to the orbits of G, then the manifold  with the quotient metric has positive sectional curvature. This fact allows one to construct the classical positively curved spaces, being spheres and projective spaces, as well as these examples (Ziller 2007):

with the quotient metric has positive sectional curvature. This fact allows one to construct the classical positively curved spaces, being spheres and projective spaces, as well as these examples (Ziller 2007):

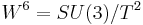

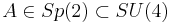

- The Berger spaces

and

and  .

.

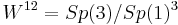

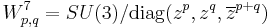

- The Wallach spaces (or the homogeneous flag manifolds):

,

,  and

and  .

.

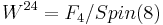

- The Aloff–Wallach spaces

.

.

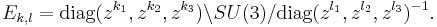

- The Eschenburg spaces

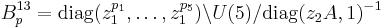

- The Bazaikin spaces

, where

, where  .

.

References

- Cheeger, Jeff; Gromoll, Detlef (1972), "On the structure of complete manifolds of nonnegative curvature", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series (Annals of Mathematics) 96 (3): 413–443, doi:10.2307/1970819, JSTOR 1970819, MR0309010.

- Gromoll, Detlef; Meyer, Wolfgang (1969), "On complete open manifolds of positive curvature", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series (Annals of Mathematics) 90 (1): 75–90, doi:10.2307/1970682, JSTOR 1970682, MR0247590.

- Milnor, John Willard (1963), Morse theory, Based on lecture notes by M. Spivak and R. Wells. Annals of Mathematics Studies, No. 51, Princeton University Press, MR0163331.

- Petersen, Peter (2006), Riemannian geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 171 (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-29246-5; 978-0-387-29246-5, MR2243772.

- Ziller, Wolfgang (2007). "Examples of manifolds with non-negative sectional curvature". arXiv:math/0701389..

See also

|

||||||||||||||